This is a fixed-text formatted version of a Jupyter notebook.

You can contribute with your own notebooks in this GitHub repository.

Source files: cta_1dc_introduction.ipynb | cta_1dc_introduction.py

CTA first data challenge logo

CTA first data challenge (1DC) with Gammapy¶

Introduction¶

The CTA observatory has started a first data challenge (“CTA 1DC”), focusing on high-level data analysis. Gammapy is a prototype for the CTA science tools (see Gammapy proceeding from ICRC 2017), and while many things are work in progress (most importantly: source and background modeling and cube analysis), you can use it already to analyse the simulated CTA data.

The main page for CTA 1DC is here: https://forge.in2p3.fr/projects/data-challenge-1-dc-1/wiki (CTA internal)

There you will find information on 1DC sky models, data access, data organisation, simulation and analysis tools, simulated observations, as well as contact information if you have any questions or comments.

This tutorial notebook¶

This notebook shows you how to get started with CTA 1DC data and what it contains.

You will learn how to use Astropy and Gammapy to:

- access event data

- access instrument response functions (IRFs)

- use index files and the

gammapy.data.DataStoreto access all data - use the observation index file to select the observations you’re interested in

- read model XML files from Python (not integrated in Gammapy yet)

This is to familiarise ourselves with the data files and to get an overview.

Further information¶

How to analyse the CTA 1DC data with Gammapy (make an image and spectrum) is shown in a second notebook cta_data_analysis.ipynb. If you prefer, you can of course just skim or skip this notebook and go straight to second one.

More tutorial notebooks for Gammapy are here, the Gammapy Sphinx docs are at at http://docs.gammapy.org If you have a Gammapy-related question, please send an email to to Gammapy mailing list at http://groups.google.com/group/gammapy (registration required) or if you have an issue or feature request, file an issue here: https://github.com/gammapy/gammapy/issues/new (free Github account required, takes 1 min to set up).

Please note that the 1DC data isn’t public and results should be shared on CTA Redmine, as described here: https://forge.in2p3.fr/projects/data-challenge-1-dc-1/wiki#Sharing-of-analysis-results. Unfortunately there’s no good way yet to share Jupyter notebooks in CTA, as there is e.g. on Github and nbviewer which can show any public noteook.

Notebook and Gammapy Setup¶

Before we get started, please execcute the following code cells.

The first one configures the notebooks so that plots are shown inline (if you don’t do this, separate windows will pop up). The second cell imports and checks the version of the packages we will use below. If you’re missing some packages, install them and then select “Kernel -> Restart” above to restart this notebook.

In case you’re new to Jupyter notebooks: to execute a cell, select it, then type “SHIFT” + “ENTER”.

In [1]:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

In [2]:

import numpy as np

import astropy

import gammapy

print('numpy:', np.__version__)

print('astropy:', astropy.__version__)

print('gammapy:', gammapy.__version__)

numpy: 1.13.3

astropy: 3.0.dev20763

gammapy: 0.7.dev5344

Getting the 1DC data¶

You can find infos how to download the 1DC data here: https://forge.in2p3.fr/projects/data-challenge-1-dc-1/wiki#Data-access

Overall it’s quite large (20 GB) and will take a while to download. You can just download a subset of the “gps”, “gc”, “egal” or “agn” datasets, the ones you’re interested in.

In this tutorial, we will only use the “gps” (Galactic center survey) dataset, so maybe you could start by downloading that first.

While you wait, we strongly recommend you go over some CTA basics as well as some Python basics to prepare yourself for this tutorial.

Got the data?

Assuming you’ve followed the instructions, you should have the

CTADATA environment variable pointing to the folder where all data

is located. (Gammapy doesn’t need or use the CALDB environment

variable.)

In [3]:

!echo $CTADATA

/Users/deil/work/cta-dc/data/1dc/1dc

In [4]:

!ls $CTADATA

caldb data index models obs

You can find a description of the directories and files here: https://forge.in2p3.fr/projects/data-challenge-1-dc-1/wiki/Data_organisation

A very detailed specification of the data formats is here: http://gamma-astro-data-formats.readthedocs.io/

But actually, instead of reading those pages, let’s just explore the data and see how to load it with Gammapy …

Before we start, just in case the commands above show that you don’t

have CTADATA set:

- you either have to exit the “jupyter notebook” command on your

terminal, set the environment variable (I’m using bash and added the

command

export CTADATA=/Users/deil/work/cta-dc/data/1dc/1dcto my~/.profilefile and then didsource ~/.profile), then re-start Jupyter and this notebook. - or you can set the environment variable by uncommentting the code in the following cell, setting the correct path, then executing it.

In [5]:

# import os

# os.environ['CTADATA'] = '/Users/deil/work/cta-dc/data/1dc/1dc'

# !echo $CTADATA

# !ls $CTADATA

Let’s have a look around at the directories and files in $CTADATA.

We will look at the data folder with events, the caldb folder

with the IRFs and the index folder with the index files. At the end,

we will also mention what the model and obs folder contains, but

they aren’t used with Gammapy, at least not at the moment.

EVENT data¶

First, the EVENT data (RA, DEC, ENERGY, TIME of each photon or hadronic

background event) is in the data/baseline folder, with one

observation per file. The “baseline” refers to the assumed CTA array

that was used to simulate the observations. The number in the filename

is the observation identifier OBS_ID of the observation.

Observations are ~ 30 minutes, pointing at a fixed location on the sky.

In [6]:

!ls $CTADATA

caldb data index models obs

In [7]:

!ls $CTADATA/data/baseline

agn egal gc gps

In [8]:

!ls $CTADATA/data/baseline/gps | head -n3

gps_baseline_110000.fits

gps_baseline_110001.fits

gps_baseline_110002.fits

In [9]:

# There's 3270 observations and 11 GB of event data for the gps dataset

!ls $CTADATA/data/baseline/gps | wc -l

!du -hs $CTADATA/data/baseline/gps

3270

11G /Users/deil/work/cta-dc/data/1dc/1dc/data/baseline/gps

Let’s open up the first event list using the Gammapy EventList

class, which contains the EVENTS table data via the table

attribute as an Astropy Table object.

In [10]:

from gammapy.data import EventList

events = EventList.read('$CTADATA/data/baseline/gps/gps_baseline_110000.fits')

print(type(events))

print(type(events.table))

<class 'gammapy.data.event_list.EventList'>

<class 'astropy.table.table.Table'>

In [11]:

# First event (using [] for "indexing")

events.table[0]

Out[11]:

| EVENT_ID | TIME | RA | DEC | ENERGY | DETX | DETY | MC_ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | deg | deg | TeV | deg | deg | ||

| uint32 | float64 | float32 | float32 | float32 | float32 | float32 | int32 |

| 1 | 662774403.255 | -173.287 | -62.4099 | 0.0486149 | 1.60795 | 0.258016 | 2 |

In [12]:

# First few events (using [] for "slicing")

events.table[:2]

Out[12]:

| EVENT_ID | TIME | RA | DEC | ENERGY | DETX | DETY | MC_ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | deg | deg | TeV | deg | deg | ||

| uint32 | float64 | float32 | float32 | float32 | float32 | float32 | int32 |

| 1 | 662774403.255 | -173.287 | -62.4099 | 0.0486149 | 1.60795 | 0.258016 | 2 |

| 2 | 662774459.184 | -172.62 | -63.0346 | 0.0611035 | 0.979058 | 0.555166 | 2 |

In [13]:

# Event times can be accessed as Astropy Time objects

print(type(events.time))

<class 'astropy.time.core.Time'>

In [14]:

events.time[:2]

Out[14]:

<Time object: scale='tt' format='mjd' value=[ 59215.50003767 59215.500685 ]>

In [15]:

# Convert event time to more human-readable format

print(events.time[:2].fits)

['2021-01-01T12:00:03.255(TT)' '2021-01-01T12:00:59.184(TT)']

In [16]:

# Event positions can be accessed as Astropy SkyCoord objects

print(type(events.radec))

events.radec[:2]

<class 'astropy.coordinates.sky_coordinate.SkyCoord'>

Out[16]:

<SkyCoord (ICRS): (ra, dec) in deg

[( 186.71313477, -62.40993118), ( 187.38043213, -63.03462601)]>

In [17]:

events.galactic[:2]

Out[17]:

<SkyCoord (Galactic): (l, b) in deg

[( 300.08953957, 0.32605543), ( 300.45042443, -0.26852334)]>

In [18]:

# The event header information is stored

# in the `events.table.meta` dictionary

print(type(events.table.meta))

<class 'collections.OrderedDict'>

In [19]:

# E.g. to get the observation pointing position in degrees:

events.table.meta['RA_PNT'], events.table.meta['DEC_PNT']

Out[19]:

(186.15609741, -64.019)

EVENT analysis example¶

As an example how to work with EVENT data, let’s look at the spatial and energy distribution of the events for a single run.

Note that EVENT data in Gammapy is just stored in an Astropy Table, which is basically a dictionary mapping column names to column data, where the column data is a Numpy array. This means you can efficienly process it from Python using any of the scientific Python tools you like (e.g. Numpy, Scipy, scikit-image, scikit-learn, …)

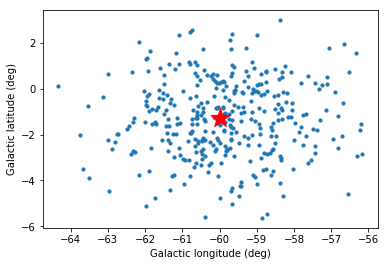

EVENT spatial distribution¶

To illustrate a bit how to work with EVENT table an header data, let’s plot the event positions as well as the pointing position.

In [20]:

# Event positions

pos = events.galactic[::300] # sub-sample every 100th event

plt.scatter(pos.l.wrap_at('180 deg').deg, pos.b.deg, s=10)

# Pointing position

pos_pnt = events.pointing_radec.galactic

plt.scatter(pos_pnt.l.wrap_at('180 deg').deg, pos_pnt.b.deg,

marker='*', s=400, c='red')

plt.xlabel('Galactic longitude (deg)')

plt.ylabel('Galactic latitude (deg)')

pos_pnt

Out[20]:

<SkyCoord (Galactic): (l, b) in deg

( 300.00001584, -1.29999832)>

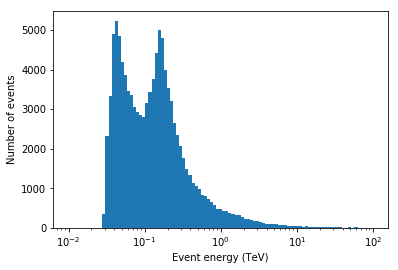

EVENT energy distribution¶

Let’s have a look at the event energy distribution.

In [21]:

energy = events.table['ENERGY'].data

energy_bins = np.logspace(-2, 2, num=100)

plt.hist(energy, bins=energy_bins)

plt.semilogx()

plt.xlabel('Event energy (TeV)')

plt.ylabel('Number of events')

Out[21]:

Text(0,0.5,'Number of events')

A double-peak, at ~ 30 GeV and ~ 100 GeV? …. let’s try to find out what’s going on …

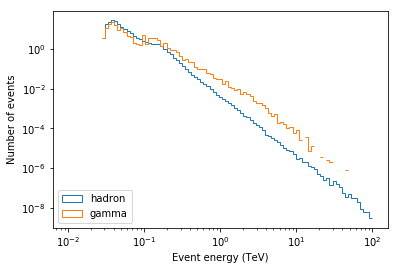

EVENT MC_ID¶

One idea could be to split the data into gamma-ray and hadronic

background events. Now from looking at the FITS header, one can see that

MC_ID == 1 is the hadronic background, and the other values are for

different gamma-ray emission components.

In [22]:

is_gamma = events.table['MC_ID'] != 1

print('Number of events: ', len(events.table))

print('Number of gammas: ', is_gamma.sum())

print('Number of hadrons: ', len(events.table) - is_gamma.sum())

Number of events: 107301

Number of gammas: 1112

Number of hadrons: 106189

In [23]:

energy = events.table['ENERGY'].data

energy_bins = np.logspace(-2, 2, num=100)

opts = dict(bins=energy_bins, normed=True, histtype='step')

plt.hist(energy[~is_gamma], label='hadron', **opts)

plt.hist(energy[is_gamma], label='gamma', **opts)

plt.loglog()

plt.xlabel('Event energy (TeV)')

plt.ylabel('Number of events')

plt.legend()

Out[23]:

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x117b49588>

As expected, the energy spectra are roughly power-laws. When plotting in log-log, one can see that the spectra are roughly power-laws (as expected), and the “double peak” we saw before looks more like a “double energy threshold” pattern. It’s there for gammas and background, and below 100 GeV the signal to background ratio is lower.

What we’re seeing here is the result of a mixed-array in CTA with LSTs, MSTs and SSTs, which have different energy thresholds:

- ~ 30 GeV is the energy threshold of the LSTs

- ~ 100 GeV is the energy threshold of the MSTs

- the energy threshold of the SSTs is at a few TeV and doesn’t show up as a clear feature in the gamma and background energy distribution (probably the rise in slope in gamma in the 1-10 TeV range is due to the SSTs).

Let’s look a little deeper and also check the event offset distribution in the field of view …

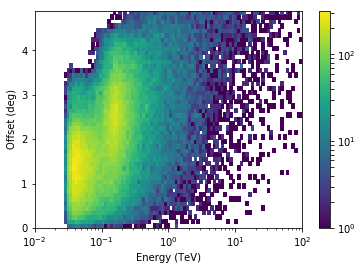

EVENT FOV offset¶

The event position and offset in the field of view (FOV) can be computed from the event RA, DEC position and the observation pointing RA, DEC position.

But actually, the field of view position is stored as extra columns in

the EVENT list: DETX and DETY (angles in degree, I think RA /

DEC aligned field of view system).

I presume (hope) this unnecessary information will be dropped from the CTA event lists in the future to save some space (make the CTA DL3 data ~25% smaller), but for now, let’s use those columns to compute the field of view offset and look at the offset-energy distribution of the events.

In [24]:

energy_bins = 10 ** np.linspace(-2, 2, 100)

offset_bins = np.arange(0, 5, 0.1)

t = events.table

offset = np.sqrt(t['DETX'] ** 2 + t['DETY'] ** 2)

hist = np.histogram2d(

x=t['ENERGY'], y=offset,

bins=(energy_bins, offset_bins),

)[0].T

from matplotlib.colors import LogNorm

plt.pcolormesh(energy_bins, offset_bins,

hist, norm=LogNorm())

plt.semilogx()

plt.colorbar()

plt.xlabel('Energy (TeV)')

plt.ylabel('Offset (deg)')

Out[24]:

Text(0,0.5,'Offset (deg)')

So the CTA field of view increases with energy in steps. The energy distribution we saw before was the combination of the energy distribution at all offsets. Even at a single offset, the double energy-threshold at ~ 30 GeV and ~ 100 GeV is present.

Stacking EVENTS tables¶

As a final example of how to work with event lists, here’s now to apply arbitrary event selections and how to stack events tables from several observations into a single event list.

We will just use astropy.table.Table directly, not go via the

gammapy.data.EventList class. Note that you can always make an

EventList object from a Table object via

event_list = EventList(table). One point to keep in mind is that

Table.read doesn’t resolve environment variables in filenames, so

we’ll use the Python standard library os package to construct the

filenames.

In [25]:

import os

from astropy.table import Table

from astropy.table import vstack as table_vstack

filename = os.path.join(os.environ['CTADATA'], 'data/baseline/gps/gps_baseline_110000.fits')

t1 = Table.read(filename, hdu='EVENTS')

filename = os.path.join(os.environ['CTADATA'], 'data/baseline/gps/gps_baseline_110001.fits')

t2 = Table.read(filename, hdu='EVENTS')

tables = [t1, t2]

table = table_vstack(tables, metadata_conflicts='silent')

In [26]:

print('Number of events: ', len(table))

Number of events: 214675

In [27]:

# Let's select gamma rays with energy above 10 TeV

mask_mc_id = table['MC_ID'] != 1

mask_energy = table['ENERGY'] > 10

mask = mask_mc_id & mask_energy

table2 = table[mask]

print('Number of events after selection:', len(table2))

Number of events after selection: 45

When processing a lot or all of the 1DC events, you would write a for loop, and apply the event selection before putting the table in the list of tables, or you might run out of memory. An example is here.

That’s all for EVENTS. You now know what every column in the event

table contains, and how to work with event list tables using

gammapy.data.EventList and astropy.table.Table.

Just in case that there is some observation parameter in the FITS EVENTS

header that you’re interested in, you can find the full description of

the keys you can access via the events.table.meta dictionary

here.

IRFs¶

The CTA instrument reponse functions (IRFs) are given as FITS files in

the caldb folder.

Note that this is not realistic. Real CTA data at the DL3 level (what we have here, what users get) will mostly likely have per-observation or per-time interval IRFs, and the IRFs will not be stored in a separate CALDB folder, but distributed with the EVENTS (probably in the same file, or at least in the same folder, so that it’s together).

For now, the EVENT to IRF association (i.e. which IRF is the right one

for given EVENTS) is done by index files. We will discuss those in the

next section, but before we do, let’s look at the CTA IRFs for one given

configuration: South_z20_50h.

In [28]:

!(cd $CTADATA && tree caldb)

caldb

└── data

└── cta

└── 1dc

├── bcf

│ ├── North_z20_50h

│ │ └── irf_file.fits

│ ├── North_z40_50h

│ │ └── irf_file.fits

│ ├── South_z20_50h

│ │ └── irf_file.fits

│ └── South_z40_50h

│ └── irf_file.fits

└── caldb.indx

8 directories, 5 files

In [29]:

# Let's look at the content of one of the IRF FITS files.

# IRFs are stored in `BinTable` HDUs in a weird format

# that you don't need to care about because it's implemented in Gammapy

irf_filename = os.path.join(os.environ['CTADATA'], 'caldb/data/cta/1dc/bcf/South_z20_50h/irf_file.fits')

from astropy.io import fits

hdu_list = fits.open(irf_filename)

hdu_list.info()

Filename: /Users/deil/work/cta-dc/data/1dc/1dc/caldb/data/cta/1dc/bcf/South_z20_50h/irf_file.fits

No. Name Ver Type Cards Dimensions Format

0 PRIMARY 1 PrimaryHDU 8 ()

1 EFFECTIVE AREA 1 BinTableHDU 53 1R x 5C [42E, 42E, 6E, 6E, 252E]

2 POINT SPREAD FUNCTION 1 BinTableHDU 70 1R x 10C [25E, 25E, 6E, 6E, 150E, 150E, 150E, 150E, 150E, 150E]

3 ENERGY DISPERSION 1 BinTableHDU 56 1R x 7C [500E, 500E, 300E, 300E, 6E, 6E, 900000E]

4 BACKGROUND 1 BinTableHDU 59 1R x 7C [36E, 36E, 36E, 36E, 21E, 21E, 27216E]

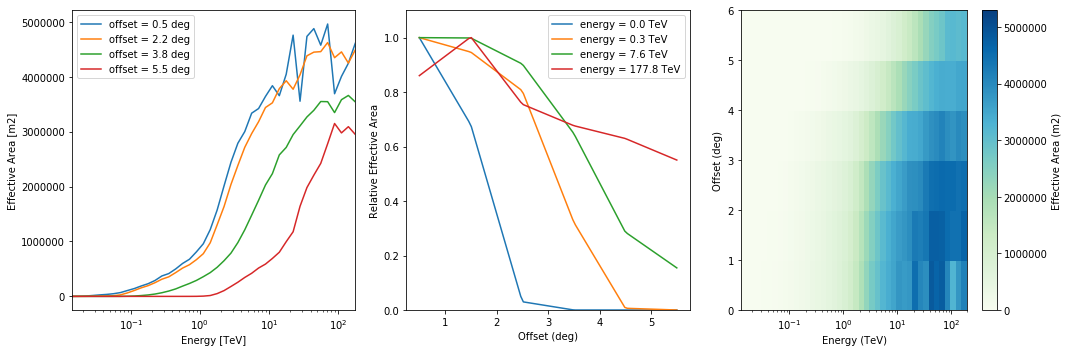

Effective area¶

The effective area is given as a 2-dim array with energy and field of view offset axes.

In [30]:

from gammapy.irf import EffectiveAreaTable2D

aeff = EffectiveAreaTable2D.read(irf_filename, hdu='EFFECTIVE AREA')

print(type(aeff))

print(type(aeff.data))

<class 'gammapy.irf.effective_area.EffectiveAreaTable2D'>

<class 'gammapy.utils.nddata.NDDataArray'>

In [31]:

print(aeff.data)

NDDataArray summary info

energy : size = 42, min = 0.014 TeV, max = 177.828 TeV

offset : size = 6, min = 0.500 deg, max = 5.500 deg

Data : size = 252, min = 0.000 m2, max = 5371581.000 m2

In [32]:

aeff.peek()

In [33]:

# What is the on-axis effective area at 10 TeV?

aeff.data.evaluate(energy='10 TeV', offset='0 deg').to('km2')

Out[33]:

In [34]:

# This is how you slice out an `EffectiveAreaTable` object

# at a given field of view offset for analysis

aeff.to_effective_area_table(offset='1 deg')

Out[34]:

<gammapy.irf.effective_area.EffectiveAreaTable at 0x11910aba8>

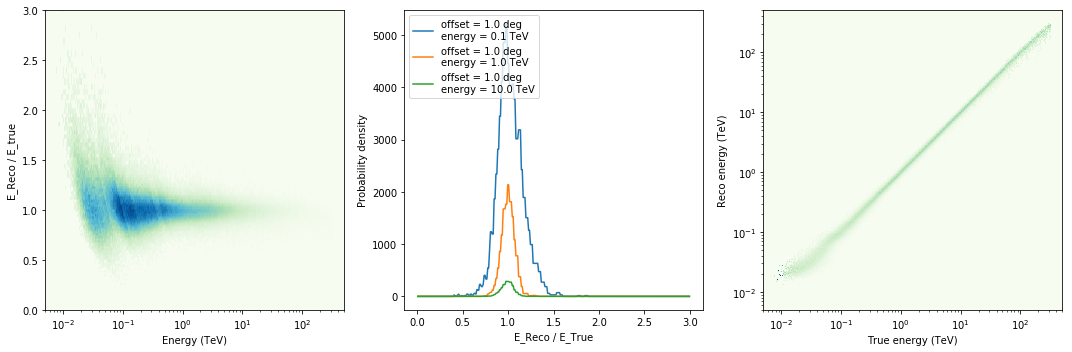

Energy dispersion¶

Let’s have a look at the CTA energy dispersion with three axes: true energy, fov offset and migra = e_reco / e_true and has dP / dmigra as value.

Similar to the event energy distribution above, we can see the mixed-telescope array reflected in the EDISP. At low energies the events are only detected and reconstructed by the LSTs. At ~100 GeV, the MSTs take over and EDISP is chaotic in the ~ 50 GeV to 100 GeV energy range. So it can be useful to have quick access to IRFs like with Gammapy (e.g. for spectral line searches in this case), even if for 95% of science analyses users later won’t have to look at the IRFs and just trust that everything is working.

In [35]:

from gammapy.irf import EnergyDispersion2D

edisp = EnergyDispersion2D.read(irf_filename, hdu='ENERGY DISPERSION')

print(type(edisp))

print(type(edisp.data))

<class 'gammapy.irf.energy_dispersion.EnergyDispersion2D'>

<class 'gammapy.utils.nddata.NDDataArray'>

In [36]:

print(edisp.data)

NDDataArray summary info

e_true : size = 500, min = 0.005 TeV, max = 495.450 TeV

migra : size = 300, min = 0.005, max = 2.995

offset : size = 6, min = 0.500 deg, max = 5.500 deg

Data : size = 900000, min = 0.000, max = 10595.855

In [37]:

edisp.peek()

/Users/deil/Library/Python/3.6/lib/python/site-packages/astropy/units/quantity.py:635: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in true_divide

result = super().__array_ufunc__(function, method, *arrays, **kwargs)

In [38]:

# This is how for analysis you could slice out an `EnergyDispersion`

# object at a given offset:

edisp.to_energy_dispersion(offset='0 deg')

/Users/deil/Library/Python/3.6/lib/python/site-packages/astropy/units/quantity.py:635: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in true_divide

result = super().__array_ufunc__(function, method, *arrays, **kwargs)

Out[38]:

<gammapy.irf.energy_dispersion.EnergyDispersion at 0x119581dd8>

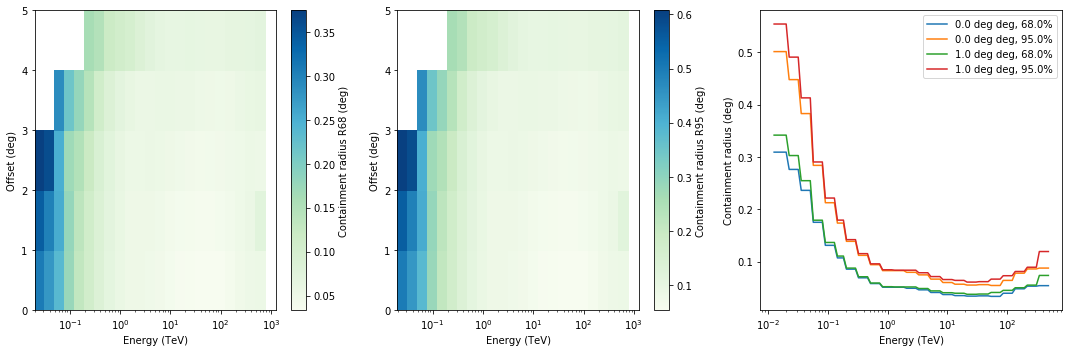

Point spread function¶

The point spread function (PSF) in this case is given as an analytical Gaussian model.

In [39]:

from gammapy.irf import EnergyDependentMultiGaussPSF

psf = EnergyDependentMultiGaussPSF.read(irf_filename, hdu='POINT SPREAD FUNCTION')

print(psf.info())

Summary PSF info

----------------

Theta : size = 6, min = 0.000 deg, max = 5.000 deg

Energy hi : size = 25, min = 0.020 TeV, max = 1258.925 TeV

Energy lo : size = 25, min = 0.013 TeV, max = 794.328 TeV

Safe energy threshold lo: 0.100 TeV

Safe energy threshold hi: 100.000 TeV

68% containment radius at theta = 0.0 deg and E = 1.0 TeV: 0.05099999 deg

68% containment radius at theta = 0.0 deg and E = 10.0 TeV: 0.03700000 deg

95% containment radius at theta = 0.0 deg and E = 1.0 TeV: 0.08269457 deg

95% containment radius at theta = 0.0 deg and E = 10.0 TeV: 0.05999410 deg

In [40]:

psf.peek()

In [41]:

# This is how for analysis you could slice out the PSF

# at a given field of view offset

psf.to_energy_dependent_table_psf('1 deg')

Out[41]:

<gammapy.irf.psf_table.EnergyDependentTablePSF at 0x11a7aa908>

Background¶

The hadronic background for CTA DC-1 is given as a template model with

an absolute rate that depends on energy, detx and dety. The

coordinates detx and dety are angles in the “field of view”

coordinate frame.

Note that really the background model for DC-1 and most CTA IRFs produced so far are radially symmetric, i.e. only depend on the FOV offset. The background model here was rotated to fill the FOV in a rotationally symmetric way, for no good reason.

In [42]:

from gammapy.irf import Background3D

bkg = Background3D.read(irf_filename, hdu='BACKGROUND')

print(bkg)

Background3D

NDDataArray summary info

energy : size = 21, min = 0.016 TeV, max = 158.489 TeV

detx : size = 36, min = -5.833 deg, max = 5.833 deg

dety : size = 36, min = -5.833 deg, max = 5.833 deg

Data : size = 27216, min = 0.000 1 / (MeV s sr), max = 0.421 1 / (MeV s sr)

In [43]:

# TODO: implement a peek method for Background3D

# bkg.peek()

In [44]:

bkg.data.evaluate(energy='3 TeV', detx='1 deg', dety='0 deg')

Out[44]:

Index files and DataStore¶

As we saw, you can access all of the CTA data using Astropy and Gammapy.

But wouldn’t it be nice if there were a better, simpler way?

Imagine what life could be like if you had a butler that knows where all the files and HDUs are, and hands you the 1DC data on a silver platter, you just have to ask for it.

gammapy.data.DataStore - your butler for CTA data

Well, the butler exists. He’s called gammapy.data.DataStore and he

keeps track of the data using index files.

Index files¶

The files with in the index folder with names obs-index.fits.gz

and hdu-index.fits.gz are so called “observation index files” and

“HDU index files”.

- The purpose of observation index files is to get a table of available observations, with the most relevant parameters commonly used for observation selection (e.g. pointing position or observation time). Their format is described in detail here.

- The purpose of HDU index files is to locate all FITS header data units (HDUs) for a given observation. At the moment, for each observation, there are six relevant HDUs: EVENTS, GTI, AEFF, EDISP, PSF and BKG. The format is described in detail here.

For 1DC there is one set of index files per simulated dataset, as well as a set of index files listing all available data in the all directory.

Side comment: if you have data, but no index files, you should write a Python script to make the index files. As an example, the one I used to make the index files for 1DC is here.

In [45]:

!(cd $CTADATA && tree index)

index

├── README.md

├── agn

│ ├── hdu-index.fits.gz

│ └── obs-index.fits.gz

├── all

│ ├── hdu-index.fits.gz

│ └── obs-index.fits.gz

├── egal

│ ├── hdu-index.fits.gz

│ └── obs-index.fits.gz

├── gc

│ ├── hdu-index.fits.gz

│ └── obs-index.fits.gz

└── gps

├── hdu-index.fits.gz

└── obs-index.fits.gz

5 directories, 11 files

Gammapy DataStore¶

If you want to access data and IRFs from the CTA 1DC GPS dataset, just

create a DataStore by pointing at a folder where the index files are

located.

In [46]:

from gammapy.data import DataStore

data_store = DataStore.from_dir('$CTADATA/index/gps')

In [47]:

# Print out some basic information about the available data:

data_store.info()

Data store summary info:

name: noname

HDU index table:

BASE_DIR: /Users/deil/work/cta-dc/data/1dc/1dc/index/gps

Rows: 19620

OBS_ID: 110000 -- 113269

HDU_TYPE: ['aeff', 'bkg', 'edisp', 'events', 'gti', 'psf']

HDU_CLASS: ['aeff_2d', 'bkg_3d', 'edisp_2d', 'events', 'gti', 'psf_3gauss']

Observation table:

Number of observations: 3270

In [48]:

# The observation index is loaded as a table

print('Number of observations: ', len(data_store.obs_table))

print(data_store.obs_table.colnames)

print('Total observation time (hours): ', data_store.obs_table['ONTIME'].sum() / 3600)

Number of observations: 3270

['OBS_ID', 'RA_PNT', 'DEC_PNT', 'GLON_PNT', 'GLAT_PNT', 'ZEN_PNT', 'ALT_PNT', 'AZ_PNT', 'ONTIME', 'LIVETIME', 'DEADC', 'TSTART', 'TSTOP', 'DATE_OBS', 'TIME_OBS', 'DATE_END', 'TIME_END', 'N_TELS', 'OBJECT', 'CALDB', 'IRF', 'EVENTS_FILENAME', 'EVENT_COUNT']

Total observation time (hours): 1635.0

In [49]:

# The HDU index is loaded as a table

print(len(data_store.hdu_table))

print(data_store.hdu_table.colnames)

19620

['OBS_ID', 'HDU_TYPE', 'HDU_CLASS', 'FILE_DIR', 'FILE_NAME', 'HDU_NAME']

In [50]:

# Of course, you can look at the tables if you like

# data_store.obs_table[:10].show_in_browser(jsviewer=True)

# data_store.hdu_table[:10].show_in_browser(jsviewer=True)

Select observations¶

With data_store.obs_table you have a table with the most common

per-observation parameters that are used for observation selection.

Using Python / Table methods it’s easy to apply any selection you like,

always with the goal of making a list or array of OBS_ID, which is

then the input to analysis.

For the current 1DC dataset it’s pretty simple, because the only quantities useful for selection are: * pointing position * which irf (i.e. array / zenith angle)

With real data, there will be more parameters of interest, such as data quality, observation duration, zenith angle, time of observation, …

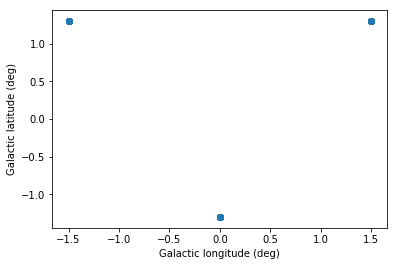

Let’s look at one example: select observations that are at offset 1 to 2 deg from the Galactic center.

In [51]:

from astropy.coordinates import SkyCoord

table = data_store.obs_table

pos_obs = SkyCoord(table['GLON_PNT'], table['GLAT_PNT'], frame='galactic', unit='deg')

pos_target = SkyCoord(0, 0, frame='galactic', unit='deg')

offset = pos_target.separation(pos_obs).deg

mask = (1 < offset) & (offset < 2)

table = table[mask]

print('Number of selected observations: ', len(table))

Number of selected observations: 57

In [52]:

# Look at the first few

table[['OBS_ID', 'GLON_PNT', 'GLAT_PNT', 'IRF']][:5]

Out[52]:

| OBS_ID | GLON_PNT | GLAT_PNT | IRF |

|---|---|---|---|

| int64 | float64 | float64 | bytes13 |

| 110380 | 359.999991204 | -1.29999593791 | South_z20_50h |

| 110381 | 359.999991204 | -1.29999593791 | South_z20_50h |

| 110382 | 359.999991204 | -1.29999593791 | South_z20_50h |

| 110383 | 359.999991204 | -1.29999593791 | South_z20_50h |

| 110384 | 359.999991204 | -1.29999593791 | South_z20_50h |

In [53]:

# Check which IRFs were used ... it's all south and 20 deg zenith angle

set(table['IRF'])

Out[53]:

{'South_z20_50h'}

In [54]:

# Check the pointing positions

# The grid pointing positions at GLAT = +- 1.2 deg are visible

from astropy.coordinates import Angle

plt.scatter(Angle(table['GLON_PNT'], unit='deg').wrap_at('180 deg'), table['GLAT_PNT'])

plt.xlabel('Galactic longitude (deg)')

plt.ylabel('Galactic latitude (deg)')

Out[54]:

Text(0,0.5,'Galactic latitude (deg)')

Load data¶

Once you have selected the observations of interest, use the

DataStore to load the data and IRF for those observations. Let’s say

we’re interested in OBS_ID=110000.

In [55]:

obs = data_store.obs(obs_id=110000)

In [56]:

print(obs)

Info for OBS_ID = 110000

- Start time: 59215.50

- Pointing pos: RA 186.16 deg / Dec -64.02 deg

- Observation duration: 1800.0 s

- Dead-time fraction: 2.000 %

In [57]:

obs.events

Out[57]:

<gammapy.data.event_list.EventList at 0x119182b00>

In [58]:

obs.events.table[:5]

Out[58]:

| EVENT_ID | TIME | RA | DEC | ENERGY | DETX | DETY | MC_ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | deg | deg | TeV | deg | deg | ||

| uint32 | float64 | float32 | float32 | float32 | float32 | float32 | int32 |

| 1 | 662774403.255 | -173.287 | -62.4099 | 0.0486149 | 1.60795 | 0.258016 | 2 |

| 2 | 662774459.184 | -172.62 | -63.0346 | 0.0611035 | 0.979058 | 0.555166 | 2 |

| 3 | 662774479.309 | -170.593 | -63.4715 | 0.046142 | 0.510549 | 1.45144 | 2 |

| 4 | 662774490.724 | -175.637 | -63.6409 | 0.0493567 | 0.36688 | -0.795908 | 2 |

| 5 | 662774506.865 | -172.124 | -63.4013 | 0.0505401 | 0.607364 | 0.7702 | 2 |

In [59]:

obs.aeff

Out[59]:

<gammapy.irf.effective_area.EffectiveAreaTable2D at 0x1190c6a58>

In [60]:

obs.edisp

Out[60]:

<gammapy.irf.energy_dispersion.EnergyDispersion2D at 0x119225898>

In [61]:

obs.psf

Out[61]:

<gammapy.irf.psf_analytical.EnergyDependentMultiGaussPSF at 0x1190cae10>

Here’s an example how to loop over many observations and analyse them: cta_1dc_make_allsky_images.py

Model XML files¶

The 1DC sky model is distributed as a set of XML files, which in turn link to a ton of other FITS and text files.

In [62]:

!ls $CTADATA/models/*.xml | xargs -n 1 basename

model_Arp220.xml

model_agn.xml

model_bkg.xml

model_dm_dSphs.xml

model_dm_gc.xml

model_fermi_bubbles.xml

model_galactic_binaries.xml

model_galactic_bright.xml

model_galactic_composite.xml

model_galactic_extended.xml

model_galactic_pulsars.xml

model_galactic_pwn.xml

model_galactic_snr.xml

model_iem.xml

models_agn.xml

models_egal.xml

models_gc.xml

models_gps.xml

In [63]:

# This is what the XML file looks like

!tail -n 20 $CTADATA/models/models_gps.xml

<parameter name="Index" value="4.58" error="0" scale="-1" min="0" max="10" free="1" />

<parameter name="Scale" value="500000" scale="1" min="0" max="10000000" free="0" />

</spectrum>

<spatialModel type="SkyDirFunction">

<parameter name="RA" value="350.69792" scale="1" min="-360" max="360" free="0" />

<parameter name="DEC" value="-49.27058" scale="1" min="-90" max="90" free="0" />

</spatialModel>

</source>

<source name="Arp220" type="PointSource" tscalc="1">

<spectrum type="PowerLaw">

<parameter name="Prefactor" value="6" error="0" scale="1e-20" min="0" free="1" />

<parameter name="Index" value="2.2" error="-0" scale="-1" min="-4.54545" max="4.54545" free="1" />

<parameter name="Scale" value="1" scale="1000000" free="0" />

</spectrum>

<spatialModel type="SkyDirFunction">

<parameter name="RA" value="233.738" scale="1" free="0" />

<parameter name="DEC" value="23.503" scale="1" free="0" />

</spatialModel>

</source>

</source_library>

At the moment, you cannot read and write these sky model XML files with Gammapy.

There are multiple reasons why this XML serialisation format isn’t implemented in Gammapy yet (all variants of “it sucks”):

- XML is tedious to read and write for humans.

- The format is too strict in places: there are many use cases where “min”, “max”, “free” and “error” aren’t needed, so it should be possible to omit them (see e.g. dummy values above)

- The parameter “scale” is an implementation detail that very few optimisers need. There’s no reason to bother all gamma-ray astronomers with separating value and scale in model input and result files.

- The “unit” is missing. Pretty important piece of information, no? All people working on IACTs use “TeV”, why should CTA be forced to use “MeV”?

- Ad-hoc extensions that keep being added and many models can’t be put in one file (see extra ASCII and FITS files with tables or other info, e.g. pulsar models added for CTA 1DC). Admittedly complex model serialisation is an intrinsically hard problem, there is not simple and flexible solution.

Also, to be honest, I also want to say / admit:

- A model serialisation format is useful, even if it will never cover all use cases (e.g. energy-dependent morphology or an AGN with a variable spectrum, or complex FOV background models).

- The Gammapy model package isn’t well-implemented or well-developed yet.

- So far users were happy to write a few lines of Python to define a model instead of XML.

- Clearly with CTA 1DC now using the XML format there’s an important reason to support it, there is the legacy of Fermi-LAT using it and ctools using / extending it for CTA.

So what now?

- In Gammapy, we have started to implement a modeling package in

gammapy.utils.modeling, with the goal of supporting this XML format as one of the serialisation formats. It’s not very far along, will be a main focus for us, help is welcome. - In addition we would like to support a second more human-friendly model format that looks something like this

- For now, you could use Gammalib to read the XML files, or you could read them directly with Python. The Python standard library contains ElementTree and there’s xmltodict which simply hands you back the XML file contents as a Python dictionary (containing a very nested hierarchical structure of Python dict and list objects and strings and numbers.

As an example, here’s how you can read an XML sky model and access the spectral parameters of one source (the last, “Arp200” visible above in the XML printout) and create a gammapy.spectrum.models.PowerLaw object.

In [64]:

# Read XML file and access spectrum parameters

from gammapy.extern import xmltodict

filename = os.path.join(os.environ['CTADATA'], 'models/models_gps.xml')

data = xmltodict.parse(open(filename).read())

data = data['source_library']['source'][-1]

data = data['spectrum']['parameter']

data

Out[64]:

[OrderedDict([('@name', 'Prefactor'),

('@value', '6'),

('@error', '0'),

('@scale', '1e-20'),

('@min', '0'),

('@free', '1')]),

OrderedDict([('@name', 'Index'),

('@value', '2.2'),

('@error', '-0'),

('@scale', '-1'),

('@min', '-4.54545'),

('@max', '4.54545'),

('@free', '1')]),

OrderedDict([('@name', 'Scale'),

('@value', '1'),

('@scale', '1000000'),

('@free', '0')])]

In [65]:

# Create a spectral model the the right units

from astropy import units as u

from gammapy.spectrum.models import PowerLaw

par_to_val = lambda par: float(par['@value']) * float(par['@scale'])

spec = PowerLaw(

amplitude=par_to_val(data[0]) * u.Unit('cm-2 s-1 MeV-1'),

index=par_to_val(data[1]),

reference=par_to_val(data[2]) * u.Unit('MeV'),

)

print(spec)

PowerLaw

Parameters:

name value error unit min max frozen

--------- ---------- ----- --------------- --- --- ------

index -2.200e+00 nan nan nan False

amplitude 6.000e-20 nan 1 / (cm2 MeV s) nan nan False

reference 1.000e+06 nan MeV nan nan True

Exercises¶

- Easy: Go over this notebook again, and change the data / code a

little bit:

- Pick another run (any run you like)

- Plot the energy-offset histogram of the events separately for gammas and background

- Medium difficulty: Find all runs within 1 deg of the Crab nebula.

- Load the “all” index file via the

DataStore, then access the.obs_table, then get an array-valuedSkyCoordwith all the observation pointing positions. - You can get the Crab nebula position with

astropy.coordinates.SkyCoordviaSkyCoord.from_name('crab') - Note that to compute the angular separation between two

SkyCoordobjects can be computed viaseparation = coord1.separation(coord2).

- Load the “all” index file via the

- Hard: Find the PeVatrons in the 1DC data, i.e. the ~ 10 sources that

are brightest at high energies (e.g. above 10 TeV).

- This is difficult, because it’s note clear how to best do this, and also because it’s time-consuming to crunch through all relevant data for any given method.

- One idea could be to go brute-force through all events, select the ones above 10 TeV and stack them all into one table. Then make an all-sky image and run a peak finder, or use an event cluster-finding method e.g. from scikit-learn.

- Another idea could be to first make a list of targets of interest, either from the CTA 1DC sky model or from gamma-cat, compute the model integral flux above 10 TeV and pick candidates that way, then run analyses.

In [66]:

# start typing here ...

What next?¶

- This notebook gave you an overview of the 1DC files and showed you have to access and work with them using Gammapy.

- To see how to do analysis, i.e. make a sky image and spectrum, see cta_data_analysis.ipynb next.