This is a fixed-text formatted version of a Jupyter notebook

You can contribute with your own notebooks in this GitHub repository.

Source files: mcmc_sampling.ipynb | mcmc_sampling.py

Fitting and error estimation with MCMC¶

Introduction¶

The goal of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms is to approximate the posterior distribution of your model parameters by random sampling in a probabilistic space. For most readers this sentence was probably not very helpful so here we’ll start straight with and example but you should read the more detailed mathematical approaches of the method here and here.

How does it work ?¶

The idea is that we use a number of walkers that will sample the posterior distribution (i.e. sample the Likelihood profile).

The goal is to produce a “chain”, i.e. a list of \(\theta\) values, where each \(\theta\) is a vector of parameters for your model. If you start far away from the truth value, the chain will take some time to converge until it reaches a stationary state. Once it has reached this stage, each successive elements of the chain are samples of the target posterior distribution. This means that, once we have obtained the chain of samples, we have everything we need. We can compute the distribution of each parameter by simply approximating it with the histogram of the samples projected into the parameter space. This will provide the errors and correlations between parameters.

Now let’s try to put a picture on the ideas described above. With this notebook, we have simulated and carried out a MCMC analysis for a source with the following parameters: \(Index=2.0\), \(Norm=5\times10^{-12}\) cm\(^{-2}\) s\(^{-1}\) TeV\(^{-1}\), \(Lambda =(1/Ecut) = 0.02\) TeV\(^{-1}\) (50 TeV) for 20 hours.

The results that you can get from a MCMC analysis will look like this :

On the first two top panels, we show the pseudo-random walk of one walker from an offset starting value to see it evolve to a better solution. In the bottom right panel, we show the trace of each 16 walkers for 500 runs (the chain described previsouly). For the first 100 runs, the parameter evolve towards a solution (can be viewed as a fitting step). Then they explore the local minimum for 400 runs which will be used to estimate the parameters correlations and errors. The choice of the Nburn value (when walkers have reached a stationary stage) can be done by eye but you can also look at the autocorrelation time.

Why should I use it ?¶

When it comes to evaluate errors and investigate parameter correlation, one typically estimate the Likelihood in a gridded search (2D Likelihood profiles). Each point of the grid implies a new model fitting. If we use 10 steps for each parameters, we will need to carry out 100 fitting procedures.

Now let’s say that I have a model with \(N\) parameters, we need to carry out that gridded analysis \(N*(N-1)\) times. So for 5 free parameters you need 20 gridded search, resulting in 2000 individual fit. Clearly this strategy doesn’t scale well to high-dimensional models.

Just for fun: if each fit procedure takes 10s, we’re talking about 5h of computing time to estimate the correlation plots.

There are many MCMC packages in the python ecosystem but here we will focus on emcee, a lightweight Python package. A description is provided here : Foreman-Mackey, Hogg, Lang & Goodman (2012).

[1]:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

[2]:

import numpy as np

import astropy.units as u

from astropy.coordinates import SkyCoord

from gammapy.irf import load_cta_irfs

from gammapy.maps import WcsGeom, MapAxis

from gammapy.modeling.models import (

ExpCutoffPowerLawSpectralModel,

GaussianSpatialModel,

SkyModel,

)

from gammapy.cube.simulate import simulate_dataset

from gammapy.modeling.sampling import (

run_mcmc,

par_to_model,

plot_corner,

plot_trace,

)

[3]:

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

Simulate an observation¶

Here we will start by simulating an observation using the simulate_dataset method.

[4]:

irfs = load_cta_irfs(

"$GAMMAPY_DATA/cta-1dc/caldb/data/cta/1dc/bcf/South_z20_50h/irf_file.fits"

)

[5]:

# Define sky model to simulate the data

spatial_model = GaussianSpatialModel(

lon_0="0 deg", lat_0="0 deg", sigma="0.2 deg", frame="galactic"

)

spectral_model = ExpCutoffPowerLawSpectralModel(

index=2,

amplitude="3e-12 cm-2 s-1 TeV-1",

reference="1 TeV",

lambda_="0.05 TeV-1",

)

sky_model_simu = SkyModel(

spatial_model=spatial_model, spectral_model=spectral_model

)

print(sky_model_simu)

SkyModel

name value error unit min max frozen

--------- --------- ----- -------------- ---------- --------- ------

lon_0 0.000e+00 nan deg nan nan False

lat_0 0.000e+00 nan deg -9.000e+01 9.000e+01 False

sigma 2.000e-01 nan deg 0.000e+00 nan False

e 0.000e+00 nan 0.000e+00 1.000e+00 True

phi 0.000e+00 nan deg nan nan True

index 2.000e+00 nan nan nan False

amplitude 3.000e-12 nan cm-2 s-1 TeV-1 nan nan False

reference 1.000e+00 nan TeV nan nan True

lambda_ 5.000e-02 nan TeV-1 nan nan False

alpha 1.000e+00 nan nan nan True

[6]:

# Define map geometry

axis = MapAxis.from_edges(

np.logspace(-1, 2, 30), unit="TeV", name="energy", interp="log"

)

geom = WcsGeom.create(

skydir=(0, 0), binsz=0.05, width=(2, 2), coordsys="GAL", axes=[axis]

)

# Define some observation parameters

pointing = SkyCoord(0 * u.deg, 0 * u.deg, frame="galactic")

dataset = simulate_dataset(

sky_model_simu, geom, pointing, irfs, livetime=20 * u.h, random_state=42

)

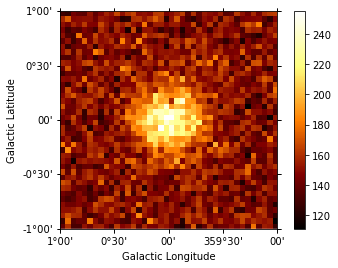

[7]:

dataset.counts.sum_over_axes().plot(add_cbar=True);

[8]:

# If you want to fit the data for comparison with MCMC later

# fit = Fit(dataset)

# result = fit.run(optimize_opts={"print_level": 1})

Estimate parameter correlations with MCMC¶

Now let’s analyse the simulated data. Here we just fit it again with the same model we had before as a starting point. The data that would be needed are the following: - counts cube, psf cube, exposure cube and background model

Luckily all those maps are already in the Dataset object.

We will need to define a Likelihood function and define priors on parameters. Here we will assume a uniform prior reading the min, max parameters from the sky model.

Define priors¶

This steps is a bit manual for the moment until we find a better API to define priors. Note the you need to define priors for each parameter otherwise your walkers can explore uncharted territories (e.g. negative norms).

[9]:

# Define the free parameters and min, max values

dataset.parameters["sigma"].frozen = True

dataset.parameters["lon_0"].frozen = True

dataset.parameters["lat_0"].frozen = True

dataset.parameters["amplitude"].frozen = False

dataset.parameters["index"].frozen = False

dataset.parameters["lambda_"].frozen = False

dataset.background_model.parameters["norm"].frozen = True

dataset.background_model.parameters["tilt"].frozen = True

dataset.background_model.parameters["norm"].min = 0.5

dataset.background_model.parameters["norm"].max = 2

dataset.parameters["index"].min = 1

dataset.parameters["index"].max = 5

dataset.parameters["lambda_"].min = 1e-3

dataset.parameters["lambda_"].max = 1

dataset.parameters["amplitude"].min = (

0.01 * dataset.parameters["amplitude"].value

)

dataset.parameters["amplitude"].max = (

100 * dataset.parameters["amplitude"].value

)

dataset.parameters["sigma"].min = 0.05

dataset.parameters["sigma"].max = 1

# Setting amplitude init values a bit offset to see evolution

# Here starting close to the real value

dataset.parameters["index"].value = 2.0

dataset.parameters["amplitude"].value = 3.2e-12

dataset.parameters["lambda_"].value = 0.05

print(dataset.models)

print("stat =", dataset.stat_sum())

SkyModels

Component 0: SkyModel

name value error unit min max frozen

--------- --------- ----- -------------- ---------- --------- ------

lon_0 0.000e+00 nan deg nan nan True

lat_0 0.000e+00 nan deg -9.000e+01 9.000e+01 True

sigma 2.000e-01 nan deg 5.000e-02 1.000e+00 True

e 0.000e+00 nan 0.000e+00 1.000e+00 True

phi 0.000e+00 nan deg nan nan True

index 2.000e+00 nan 1.000e+00 5.000e+00 False

amplitude 3.200e-12 nan cm-2 s-1 TeV-1 3.000e-14 3.000e-10 False

reference 1.000e+00 nan TeV nan nan True

lambda_ 5.000e-02 nan TeV-1 1.000e-03 1.000e+00 False

alpha 1.000e+00 nan nan nan True

stat = -939572.3185210546

[10]:

%%time

# Now let's define a function to init parameters and run the MCMC with emcee

# Depending on your number of walkers, Nrun and dimensionality, this can take a while (> minutes)

sampler = run_mcmc(dataset, nwalkers=6, nrun=150) # to speedup the notebook

# sampler=run_mcmc(dataset,nwalkers=12,nrun=1000) # more accurate contours

INFO:gammapy.modeling.sampling:Free parameters: ['index', 'amplitude', 'lambda_']

INFO:gammapy.modeling.sampling:Starting MCMC sampling: nwalkers=6, nrun=150

INFO:gammapy.modeling.sampling: 0%

INFO:gammapy.modeling.sampling: 50%

INFO:gammapy.modeling.sampling:100% => sampling completed

CPU times: user 20.7 s, sys: 532 ms, total: 21.2 s

Wall time: 22.6 s

Plot the results¶

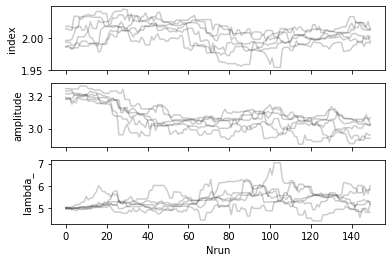

The MCMC will return a sampler object containing the trace of all walkers. The most important part is the chain attribute which is an array of shape: (nwalkers, nrun, nfreeparam)

The chain is then used to plot the trace of the walkers and estimate the burnin period (the time for the walkers to reach a stationary stage).

[11]:

plot_trace(sampler, dataset)

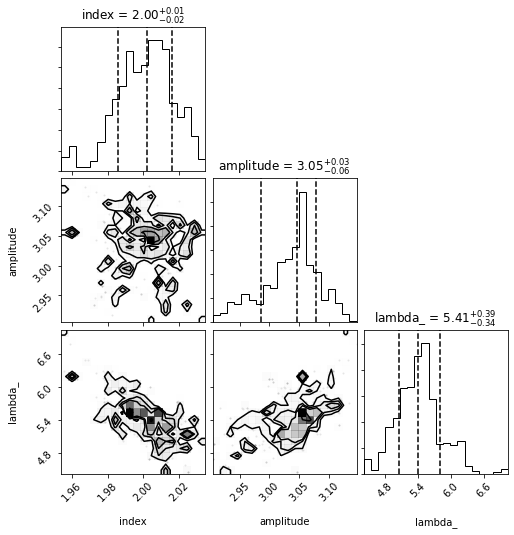

[12]:

plot_corner(sampler, dataset, nburn=50)

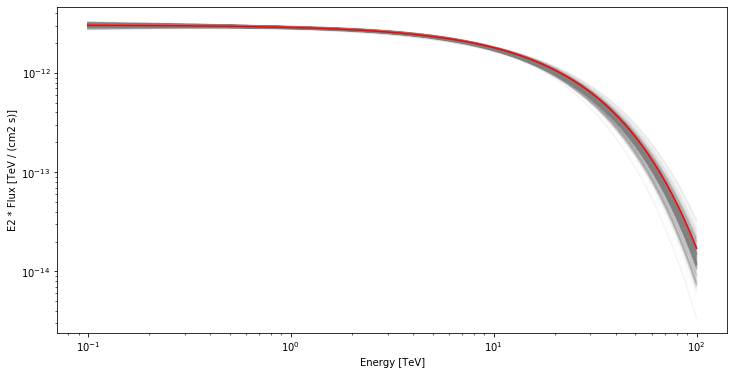

Plot the model dispersion¶

Using the samples from the chain after the burn period, we can plot the different models compared to the truth model. To do this we need to the spectral models for each parameter state in the sample.

[13]:

emin, emax = [0.1, 100] * u.TeV

nburn = 50

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(12, 6))

for nwalk in range(0, 6):

for n in range(nburn, nburn + 100):

pars = sampler.chain[nwalk, n, :]

# set model parameters

par_to_model(dataset, pars)

spectral_model = dataset.models[0].spectral_model

spectral_model.plot(

energy_range=(emin, emax),

ax=ax,

energy_power=2,

alpha=0.02,

color="grey",

)

sky_model_simu.spectral_model.plot(

energy_range=(emin, emax), energy_power=2, ax=ax, color="red"

);

Fun Zone¶

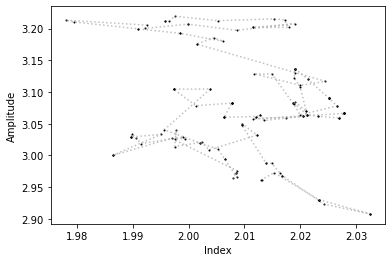

Now that you have the sampler chain, you have in your hands the entire history of each walkers in the N-Dimensional parameter space. You can for example trace the steps of each walker in any parameter space.

[14]:

# Here we plot the trace of one walker in a given parameter space

parx, pary = 0, 1

plt.plot(sampler.chain[0, :, parx], sampler.chain[0, :, pary], "ko", ms=1)

plt.plot(

sampler.chain[0, :, parx],

sampler.chain[0, :, pary],

ls=":",

color="grey",

alpha=0.5,

)

plt.xlabel("Index")

plt.ylabel("Amplitude");

PeVatrons in CTA ?¶

Now it’s your turn to play with this MCMC notebook. For example to test the CTA performance to measure a cutoff at very high energies (100 TeV ?).

After defining your Skymodel it can be as simple as this :

[15]:

# dataset = simulate_dataset(model, geom, pointing, irfs)

# sampler = run_mcmc(dataset)

# plot_trace(sampler, dataset)

# plot_corner(sampler, dataset, nburn=200)