Feldman and Cousins Confidence Intervals¶

Feldman and Cousins solved the problem on how to choose confidence intervals in

a unified way (that is without basing the choice on the data) [Feldman1998].

The functions gammapy.stats.fc_* give you access to a numerical solution to

the Feldman Cousins algorithm. It can be used for any type of statistical

distribution and is not limited to a Poisson process with background or a

Gaussian with a boundary at the origin.

The basic ingredient to fc_construct_acceptance_intervals_pdfs

is a matrix of \(P(X|\mu)\) (see e.g. equation (3.1) and (3.2) in

[Feldman1998]). Every row is a probability density function (PDF) of x and the

columns are built up by varying the signal strength \(\mu\). The other

parameter is the desired confidence level (C.L.). The function will return

another matrix of acceptance intervals where 1 means the point is part of the

acceptance interval and 0 means it is outside. This can be easily converted to

upper and lower limits (fc_get_limits), which simply connect

the outside 1s for different \(\mu\) values. An upper or lower limit is

obtained by drawing a vertical line at the measured value and calculating the

intersection (fc_find_limit).

Examples¶

Assume you have a Poisson background with known mean 3.0. We generate the matrix of \(P(X|\mu)\) like this

import gammapy.stats as gstats

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

x_bins = np.arange(0, 50)

mu_bins = np.linspace(0, 15, 15 / 0.005 + 1, endpoint=True)

matrix = [stats.poisson(mu + 3.0).pmf(x_bins) for mu in mu_bins]

Now we generate the 90% acceptance intervals and construct the lower and upper limit from them:

acceptance_intervals = gstats.fc_construct_acceptance_intervals_pdfs(matrix, 0.9)

LowerLimitNum, UpperLimitNum, _ = gstats.fc_get_limits(mu_bins, x_bins, acceptance_intervals)

Let’s say you measured x = 1, then the 90% upper limit would be:

>>> gstats.fc_find_limit(1, UpperLimitNum, mu_bins)

1.875

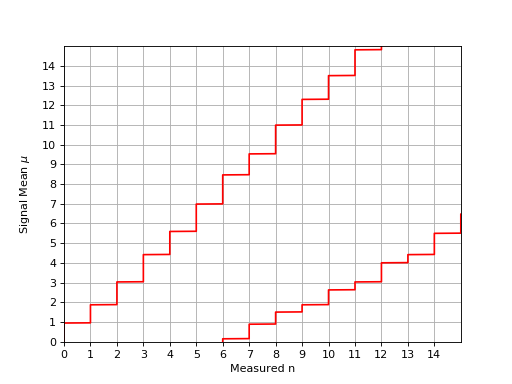

The following plot shows the confidence belt based on the Feldman and Cousins principle for a 90% confidence level for the unknown Poisson signal mean \(\mu\). It is a reproduction of Fig. 7 from [Feldman1998]. It should be noted that the plot in the paper is inconsistent with Table IV from the same paper: the lower limit is off by one bin to the left.

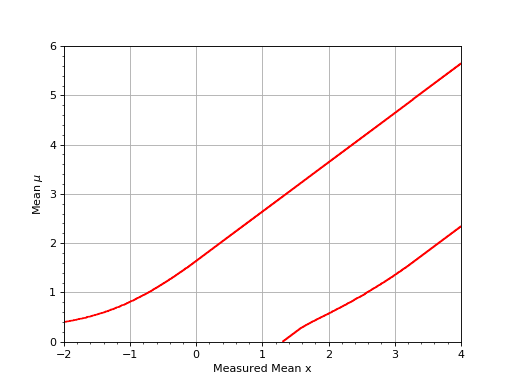

Assume you have an experiment where the observable x is simply the measured value of \(\mu\) in an experiment with a Gaussian resolution with known width \(\sigma\). The following plot shows the confidence belt based on the Feldman and Cousins principle for a 90% confidence level for the mean of the Gaussian \(\mu\), constrained to be non-negative. it reproduces Fig. 10 from [Feldman1998].

Acceptance Interval Fixing¶

Feldman and Cousins point out that sometimes the set of intersected horizontal

lines is not simply connected. These artefacts are corrected with

fc_fix_limits.

>>> gstats.fc_fix_limits(LowerLimitNum, UpperLimitNum)

The following script in the examples directory demonstrates the problem:

example_fc_demonstrate_artefact.py

For mu = 0.745 the 90% acceptance interval is [0,8] and for mu = 0.750 it is

[1,8]. A lot of the fast algorithms that do not compute the full confidence belt

will come to the conclusion that the 90% confidence interval is [0, 0.745] and

thus the upper limit when zero is measured should be 0.745 (one example is

TFeldmanCousins that comes with ROOT, but is has the additional bug of

making the confidence interval one mu bin to big, thus reporting 0.75 as upper

limit).

For mu = 1.035 the 90% acceptance interval is [0,8] again and only starting mu = 1.060 will 0 no longer be in the 90% acceptance interval. Thus the correct upper limit according to the procedure described in [Feldman1998] should be 1.055, which is also the value given in the paper (rounded to 1.06).

Sensitivity¶

[Feldman1998] also defines experimental sensitivity as the average upper limit

that would be obtained by an ensemble of experiments with the expected

background and no true signal. It can be calculated using

fc_find_average_upper_limit.

>>> gstats.fc_find_average_upper_limit(x_bins, matrix, UpperLimitNum, mu_bins)

4.41

General Case¶

In the more general case, one may not know the underlying PDF of

\(P(X|\mu)\). One way would be to generate \(P(X|\mu)\) from Monte

Carlo simulation. With a dictionary of mu values and lists of X values from

Monte Carlo one can use fc_construct_acceptance_intervals to

construct the confidence belts.

Here is an example, where the X values are generated from Monte Carlo (seed is fixed here, so the result is known):

import gammapy.stats as gstats

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

x_bins = np.linspace(-10, 10, 100, endpoint=True)

mu_bins = np.linspace(0, 8, 8 / 0.05 + 1, endpoint=True)

np.random.seed(seed=1)

distribution_dict = dict((mu, [stats.norm.rvs(loc=mu, scale=1, size=5000)]) for mu in mu_bins)

acceptance_intervals = gstats.fc_construct_acceptance_intervals(distribution_dict, x_bins, 0.6827)

LowerLimitNum, UpperLimitNum, _ = gstats.fc_get_limits(mu_bins, x_bins, acceptance_intervals)

mu_upper_limit = gstats.fc_find_limit(1.7, UpperLimitNum, mu_bins)

# mu_upper_limit == 2.7

Verification¶

To verify that the numerical solution is working, the example plots can also be

produced using the analytical solution. They look consistent. The scripts for

the analytical solution are given in the examples directory:

example_fc_poisson_analytical.py

example_fc_gauss_analytical.py